1915

Diaghilev's Ballet Russes

"I was positively uninterested in the dance."

Michael and Vera Vokin, Russian court dancers, in the ballet "Scheherezade."

When Bernays took on Diaghilev's Ballet Russes American tour in 1915, he wrote, "I was given a job about which I knew nothing. In fact, I was positively uninterested in the dance." He wasn't alone. Americans thought masculine dancers were deviates, and that "dancing was not nice," and of limited interest.

Bernays began to connect ballet to something people understood and enjoyed. "First, as a novelty in art forms, a unifying of several arts; second, its appeal to special groups; third, its direct impact on American life, on design and color in American products; and fourth, its personalities."

Beginning with newspapers, Bernays developed a four-page newsletter for editorial writers, local managers and others, containing photographs and stories of dancers, costumes, and composers. Articles were targeted to his four themes and audiences. For example, the "women's pages" received articles on costumes, fabric, and fashion design; the Sunday supplements received full-color photos.

A Bakst creation for Dance Guerriere Caucasienne.

Magazine coverage, timed to appear just before the ballet opened, was his next approach. Bernays tailored his stories to his editors. When Ladies Home Journal said that they couldn't show photographs of dancers with skirts above the knees, he had artists retouch photos to bring down the hem. His abilities to understand editors' needs resulted in wide coverage: The American Hebrew, Collier's, Craftsman, Every Week, Harper's Weekly, Hearst Magazines, Harper's Bazaar, The Independent, Ladies Home Journal, Literary Digest, Munsey's, Musical America, Opera, Physical Culture, Strand, Spur, Town & Country, Vanity Fair, Vogue, and Woman's Home Companion.

Bernays created an 81-page user-friendly publicity guide for advance men to use on the tour. When a national story about the Ballet Russes appeared, advance men could tailor it for local coverage. The guide contained mimeographed pages, bios on the dancers, short notes and fillers, and even a question and answer page that asked, "Are American men ashamed to be graceful?"

He persuaded American manufacturers to make products inspired by the color and design of the sets and costumes, and national stores to advertise them. These styles became so popular that Fifth Avenue stores sold these products without Bernays's intervention. Bernays used overseas media reviews to heighten anticipation for the dancers. When they arrived at the docks in New York, a crowd was waiting. Bernays then took photos of the eager crowds and placed them in Sunday magazines throughout the country. The ballet was sold out before the opening. By the time the ballet toured American cities, demand had already dictated a second tour and little girls were dreaming of becoming ballerinas. Bernays had remolded biases to get his story told. The American view of ballet and dance was changed forever.

1917

Bernays on Broadway

The early days of Bernays's career are spent as a Broadway press agent, which eventually brings him together with leaders of the arts and entertainment communities including notables Enrico Caruso, Florenz Ziegfeld and Nijinsky. (Bernays is standing at far right.)

"In 1915 or thereabouts I became a member — a one-third owner/partner — of the Metropolitan Musical Bureau which had been established with a sanction of the Metropolitan Opera Company. My title was Publicity Manager. Caruso was one of our clients and when he sang I occasionally went on the road with him. This is a picture taken in Toledo just about when we were preparing for WWI. We were greeted in Toledo by members of our armed forces, the infantry, and to my surprise when we took this picture we found a soldier who looked like Caruso standing right in front of the car and Caruso is greeting him from the window of the automobile we were traveling in. Caruso sang next morning at the Shriners Temple."

—Edward Bernays, in a 1987 videotape housed at the Museum of Public Relations

1918

Preparing for the Paris Peace Conference

"When WWI started in 1918, like many other Americans, I wanted to enlist as a soldier but unfortunately my vision was 20/18 and nobody could enter the armed services of the Untied States whose vision was not 20/20. A few weeks after that I noted that George Creel, a member of the group that fought for greater liberalism with Ida Tarbell, Ernest Poole and others, had been appointed head of the United States Information agency called USIA and it was the first time the United States was to use ideas as weapons to win a war. I applied to the USIA to become a staff member and was accepted. I was the only person on the staff in New York that had ever had any activity in publicity, press agentry or the like. The others were mostly professors and I served in the foreign office that dealt with materials sent to other media and with overt acts to make the world safe for democracy and make this a war to end all wars. To my surprise and delight I was invited over to the Peace Conference in Paris which Woodrow Wilson was to come to and this is a picture of the various members of our group of the foreign policy office of the agency in New York. And we traveled as I recall it for 10 days on the Atlantic Ocean, landed in France and were each assigned a separate apartment in Paris and worked on Wilson's 14 Points as I said to win the war to win the morale of our allies to win over the neutrals and to deflate the morale of the enemy."

—Edward Bernays, in a 1987 videotape housed at the Museum of Public Relations

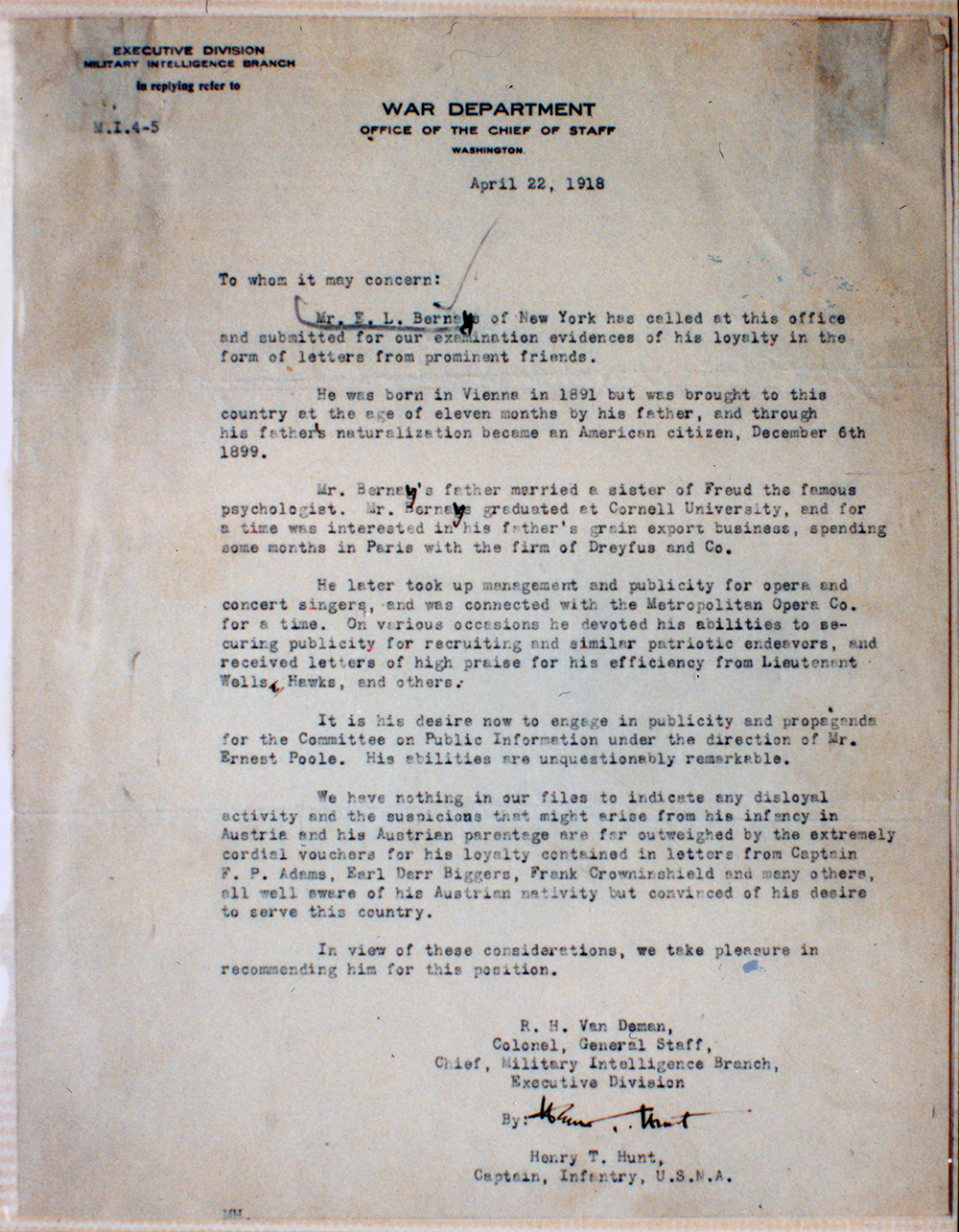

The Military Branch of the War Department clears Bernays to work for the Committee on Public Information. This letter is, in a way, an abbreviated bio of Bernays, referring both to his relationship to Sigmund Freud and his early years in the United States.

Bernays wanted to enlist as a soldier during World War I, but his military service was limited to clerk because his vision was not 20/20.

1920

NAACP Conference in Atlanta: Cilvil Rights Action Through the Media

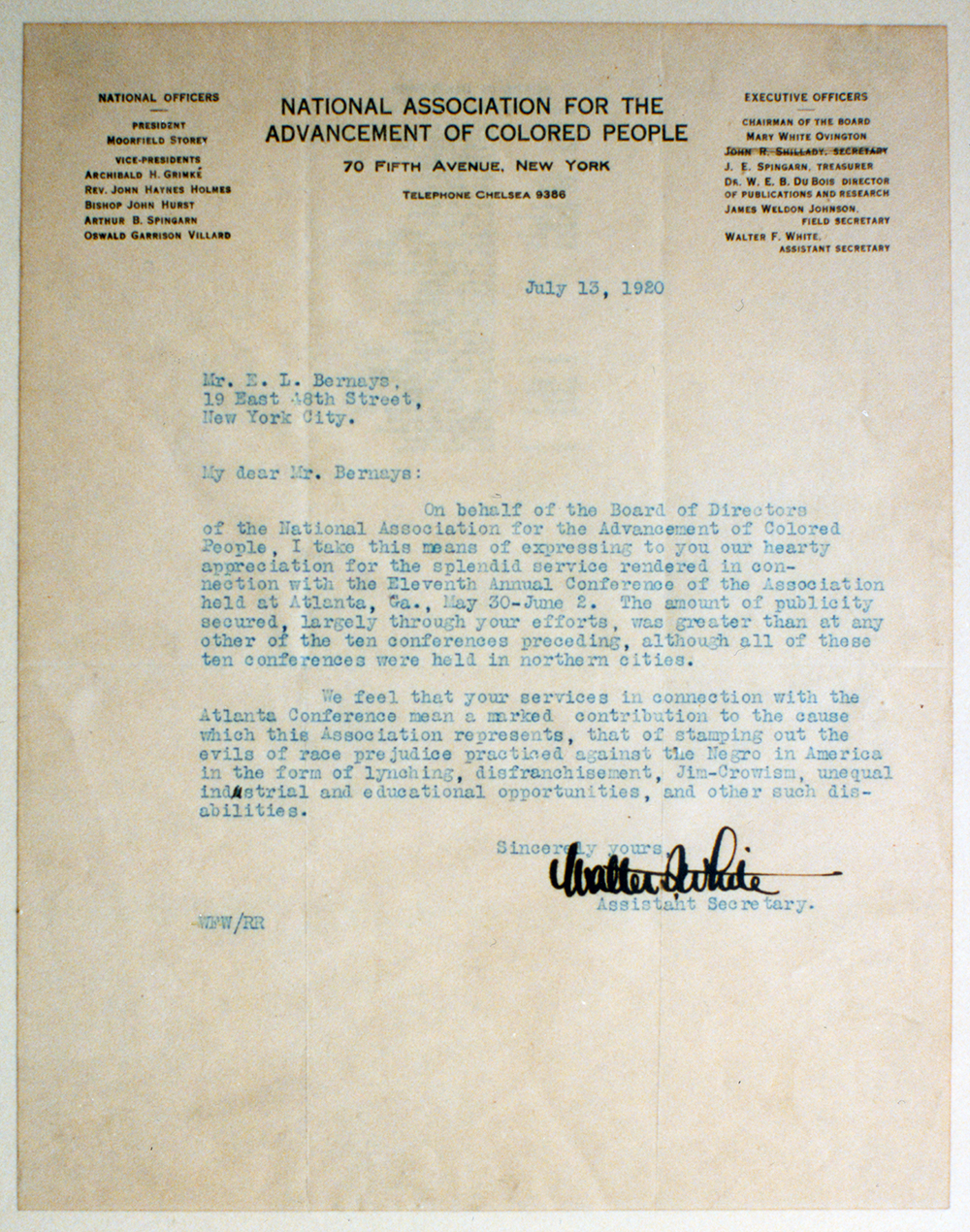

Walter F. White, assistant secretary of the NAACP expresses appreciation for Bernays’ service with connection with NAACP’s 11th annual conference in Atlanta.

When Arthur B. Spingarn, New York lawyer and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founder, asked Edward Bernays to handle publicity for the 1920 regional convention in Atlanta, the respectful term for black people was "Negro", though not too many people were using it. Affecting a major attitudinal change was to be a terrific challenge.

The goals of the campaign were to use the Atlanta Convention as "a springboard for publicity, to make the South and North realize that we are in earnest in battling for the civil rights of the Negro." These "rights" were considered revolutionary: abolish lynching, segregation, and Jim Crow railroad cars; and obtain equal education, industrial opportunities, and voting rights.

Holding the NAACP conference in Atlanta was "startling to say the least," according to The New York Times. While Bernays began contacting Northern newspapers and press services offering to cover the convention for them, his associate and future wife, Doris Fleischman, went to Atlanta to recruit Georgia's elected officials to attend the conference and show their support.

Affecting a major attitudinal change was to be a terrific challenge.

In Atlanta, Fleischman was threatened by the people opposed to "Negro rights," and the politicians were unnerved. The Governor told her that he couldn't attend the conference because he had to go duck hunting. She suggested that it might be a good idea to have the militia stand by in case of violence. He agreed.

By the time Bernays arrived from New York, the community was filled with tension and there were repeated threats of mass violence. Unintimidated, Bernays and Fleischman outlined three themes to the media:

First, "the Negro's importance to the economic development of the south." Bernays said, "This approach was based on an appeal to their (white people's) fear of losing profits if migration of workers persisted."

Second, "the less intolerant attitudes of some Southern leaders toward Negroes which would hopefully strengthen the nucleus of supporters and develop a bandwagon movement."

Third, "the support of the NAACP by important leaders in the north to induce Southern group leaders to follow their lead. Bernays had gathered statements from north leaders which he promoted in the press."

The conference was held without incident and delegates to the conference voted to send their objectives to President Wilson and to Congress. Media coverage was impressive. Atlanta's newspapers, The New York Globe, The Evening Post, The Chicago Daily, and others carried stories about the meeting and a feature outlining "progress made by Negroes from the plantation labor to business and the professions."

"For the first time in the history of the country," Bernays said, "under the dateline of the South's industrial metropolis, news was published throughout the country alerting the people of the United States that whites and negroes alike were seeking new status for the Negro."

1920

Soap and Art

There is no better public relations casebook than the work that Bernays provided for Procter and Gamble (P&G) for more than thirty years. Ranging from product publicity to national programs, Bernays used community relations, crisis communications, public affairs, and media campaigns to advance P&G's position. In both thought and action, Bernays emphasized the "coincidence of public and private interest, of the supremacy of propaganda of the deed over the propaganda of the work, of the desirability of a large corporation assuming constructive leadership in the community."

P&G, already considered innovative, hired Bernays in 1923 to provide support for advertising Ivory soap and Crisco. He began with a survey that showed a preference for "white unperfumed soap." Ivory was the only white unperfumed soap on the market and when the media reported the results, Bernays objective was met.

He used events to further obtain media coverage for Ivory: a soap yacht race in Central Park, a resolution by the Ziegfeld Follies Girls to use "nothing but warm water and pure white, unscented, floating soap on their faces," and distribution of household hints recommending pure white soap from the National Household Service. He even advocated that citizens should nurture their civic pride by washing their town statues and municipal buildings with Ivory.

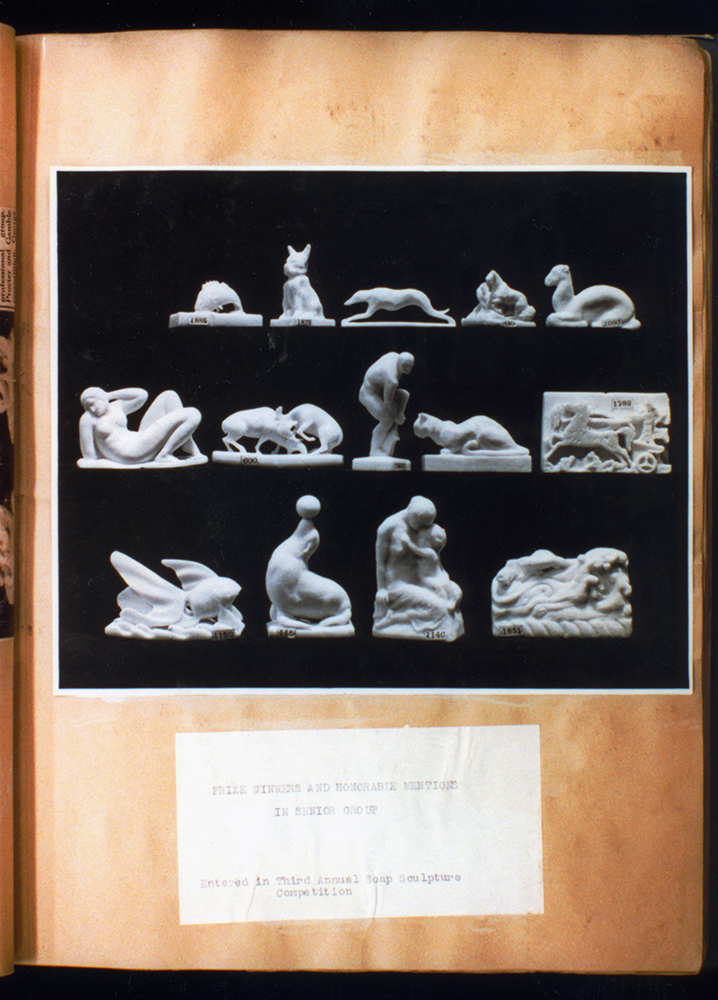

Bernays liked contests. For a quarter of a century, the National Soap Sculpture Competition in White Soap inspired millions of school children to find "creative and artistic expression... Children, the enemies of soap, would be conditioned to enjoy using Ivory." Winning sculptures were sent to national exhibitions in New York and museums around the country earning international media coverage. P&G made it an annual event, "symbolizing white floating Ivory soap."

Children, the enemies of soap, would be conditioned to enjoy using Ivory

Bernays liked contests. For a quarter of a century, the National Soap Sculpture Competition in White Soap inspired millions of school children to find "creative and artistic expression... Children, the enemies of soap, would be conditioned to enjoy using Ivory." Winning sculptures were sent to national exhibitions in New York and museums around the country earning international media coverage. P&G made it an annual event, "symbolizing white floating Ivory soap."

Brenda Putnam, American-sculptor, 1890–1975

When the Norge made the first blimp trip across the North Pole in 1926, Bernays made sure that everyone knew it used P&G glycerin. "The cooling water for the engines was mixed with glycerin at Kings Bay to prevent it from freezing," reported The New York Times, The St. Louis Dispatch and broadcast journalists across the country.

"For the first time in my life I have been exposed to the power of public opinion."

—R.R. Deupree, president of Procter & Gamble, 1943

Public Relations for P&G dramatically changed when, in 1943, Bernays accompanied R.R. Deupree, president of P&G, to Washington for a meeting on war production. They discussed public relations and Deupree was impressed. "For the first time in my life I have been exposed to the power of public opinion," said Deupree. "I realize how important it is for a corporation to have public opinion's support."

1924

Recognition Through Collaboration: Art In Industry

Cheney Brothers, a 100-year-old New York-based family silk manufacturing business, found itself losing market share. They hired art director Henry Creange to establish a sense of style for the company, and Creange hired Bernays. When they began their campaign, the French had the monopoly on style. Rather than compete, Bernays co-opted. He created the Cheney Style Service, which included a free mat service for 300 small newspapers, fashion bulletins for department store salesmen, and letters about French fashion to hundreds of newspaper editors.

A firm believer in linking celebrities and products, Bernays arranged for Cheney Brothers's oldest worker to present First Lady Mrs. Warren G. Harding with a silk dress at the White House. When this resulted in massive media coverage, he presented three lengths of silk to the textile museum in Lyons, France, where great silk was manufactured. News of the French endorsement of an American product was cabled back to American newspapers, reinforcing Cheney Brothers's and Creange's credibility.

Next, Bernays invented the "Art in Industry" medal convincing the Architectural League to give it to Henry Creange. The award publicized Cheney Brothers and initiated the concept of art in industry.

Later, when Creange was inspired by French ironwork by Edgar Brandt, Bernays arranged for art shows of Brandt's ironworks draped with Cheney Brothers silks in New York and throughout the country. Art critics applauded and again fashion press and designers endorsed Cheney Brothers.

Bernays arranged for American silks to appear in the Louvre

Continuing to look for French endorsements, Bernays arranged for American silks to be exhibited in the Louvre for the first time ever. Media coverage of the Louvre exhibition furthered Cheney Brothers as spokespeople for art in industry.

Bernays, Creange, and Cheney Brothers commissioned painter Georgia O'Keefe to create art based on the Cheney colors and her paintings were placed in store windows. Cheney Brothers sales increased and they now accepted the fact that public relations could generate sales.

Bernays represented the U.S. at the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925 (Bernays is seated near the center, his right hand at his face).

When Paris hosted the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, Bernays ensured American representation. The Exposition lasted 17 weeks; publicity lasted much longer. This was the first time the U.S. Government recognized "art in industry." U.S. participation in the Exposition also strengthened U.S.-French relations.

For many years textile, advertising, furniture, printing, and other industries reflected the Cheney Brothers's adaptation of French style. Bernays used public relations to "create acceptance of beauty as an important aspect of the manufactured product."

A firm believer in linking celebrities and products, Bernays arranged for Cheney Brothers's oldest worker to present First Lady Mrs. Warren G. Harding with a silk dress at the White House. When this resulted in massive media coverage, he presented three lengths of silk to the textile museum in Lyons, France, where great silk was manufactured. News of the French endorsement of an American product was cabled back to American newspapers, reinforcing Cheney Brothers's and Creange's credibility.

Next, Bernays invented the "Art in Industry" medal convincing the Architectural League to give it to Henry Creange. The award publicized Cheney Brothers and initiated the concept of art in industry.

Later, when Creange was inspired by French ironwork by Edgar Brandt, Bernays arranged for art shows of Brandt's ironworks draped with Cheney Brothers silks in New York and throughout the country. Art critics applauded and again fashion press and designers endorsed Cheney Brothers.

Continuing to look for French endorsements, Bernays arranged for American silks to be exhibited in the Louvre for the first time ever. Media coverage of the Louvre exhibition furthered Cheney Brothers as spokespeople for art in industry.

Bernays, Creange, and Cheney Brothers commissioned painter Georgia O'Keefe to create art based on the Cheney colors and her paintings were placed in store windows. Cheney Brothers sales increased and they now accepted the fact that public relations could generate sales.

When Paris hosted the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925, Bernays ensured American representation. The Exposition lasted 17 weeks; publicity lasted much longer. This was the first time the U.S. Government recognized "art in industry." U.S. participation in the Exposition also strengthened U.S.-French relations.

For many years textile, advertising, furniture, printing, and other industries reflected the Cheney Brothers's adaptation of French style. Bernays used public relations to "create acceptance of beauty as an important aspect of the manufactured product."

Bernays's involvement with artwork in industry on behalf of several clients leads to a communique from Eleanor Roosevelt, then First Lady of the United States on a pre-World War II platform.

1928

Warming up Calvin Coolidge

Bernays was asked to bring a celebrity group to visit the White House and demonstrate Coolidge's "warm, sympathetic personality." He decided that "stage people symbolize warmth, extroversion, and Bohemian camaraderie," and set up a star-studded breakfast at the White House. He arranged for a group of actors to take the midnight train from New York to Washington after they finished their shows. The cast included Al Jolson, Ed Wynn, The Dolly Sisters, Charlotte Greenwood, Raymond Hitchcock, and other big stars of the time.

Mrs. Coolidge greeted the guests. "I have met you all across the footlights," she said, "but it's not the same as greeting you here." The President was not quite as welcoming. "He was practically inarticulate, and no movement of any kind agitated his deadpan face," Bernays said later.

When the group lined up for breakfast photos, the President remained as grim as ever. After breakfast, the group moved to the White House lawn where Al Jolson sang "Keep Coolidge," which he had composed for the occasion. Everybody sang -- except for the President.

Despite Coolidge's demeanor, celebrity star power seems to have worked. Newspaper headlines reported, "Actor Eats Cake with the Coolidges...President Nearly Laughs...Guests Crack Dignified Jokes, Sing Song and Pledge To Support Coolidge."

Probably no one looked at Coolidge again in the same way.

1929

Torches of Freedom

By the mid-1920s smoking had become commonplace in the United States and cigarette tobacco was the most popular form of tobacco consumption. At the same time women had just won the right to vote, widows were succeeding their husbands as governors of such states as Texas and Wyoming, and more were attending college and entering the workforce. While women seemed to be making great strides in certain areas, socially they still were not able to achieve the same equality as their male counterparts. Women were only permitted to smoke in the privacy of their own homes. Public opinion and certain legislation at the time did not permit women to smoke in public, and in 1922 a woman from New York City was arrested for lighting a cigarette on the street.

George Washington Hill, president of the American Tobacco Company and an eccentric businessman, recognized that an important part of his market was not being tapped into. Hill believed that cigarette sales would soar if he could entice more women to smoke in public.

In 1928 Hill hired Bernays to expand the sales of his Lucky Strike cigarettes. Recognizing that women were still riding high on the suffrage movement, Bernays used this as the basis for his new campaign. He consulted Dr. A.A. Brill, a psychoanalyst, to find the psychological basis for women smoking. Dr. Brill determined that cigarettes which were usually equated with men, represented torches of freedom for women. The event caused a national stir and stories appeared in newspapers throughout the country. Though not doing away with the taboo completely, Bernays's efforts had a lasting effect on women smoking.

1930

Working with Eleanor Roosevelt

Left to right: Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, Frank Calderone, and Bernays.

1940s:

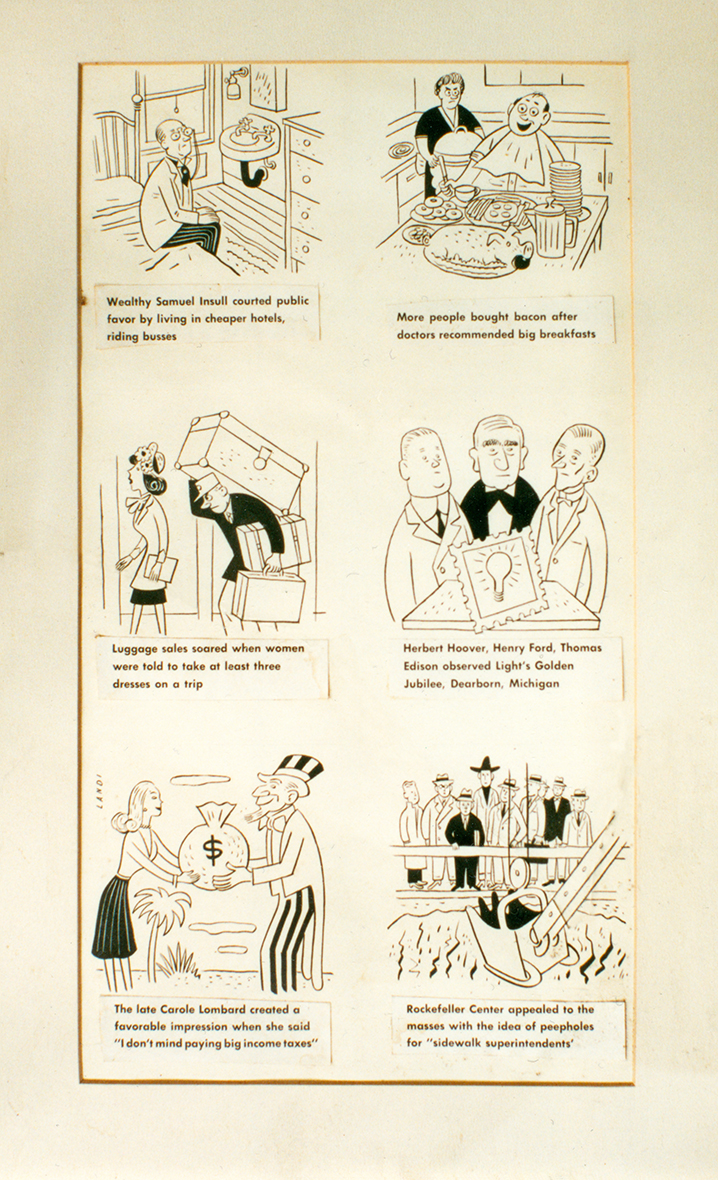

Bernays campaigns summarized in illustration

In an illustration belonging to Bernays, six of his campaigns were captured in single frame cartoons.

1940s

Ideas as Weapons

1941

Eleanor Roosevelt

Bernays's involvement with artwork in industry on behalf of several clients leads to a communique from Eleanor Roosevelt, then First Lady of the United States on a pre-World War II platform.

An in-demand guest speaker, Bernays takes part in round-table discussions and other forums. He appears, pictured center, on WNYC Radio's "Ideas Are Weapons" program along with Harry Berk and Norman Cousins of the Saturday Review.

1945

NAACP

An assignment to publicize the NAACP's first national convention held in a Southern city begins a lifelong commitment to promoting racial harmony. The Edward L. Bernays Award for leadership in promoting Negro-White relations is established by The Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America's Relations Department.

1960

Danger of Smoking

Bernays's efforts to inform the public about the dangers of smoking earn him praise from Action on Smoking & Health. He writes, "had I known in 1928 what I know today I would have refused Hill's offer." referring to his client, American Tobacco Company.

1992

The Case for Licensing

"I have spent much of my life pursuing [licensing]."

Bernays spent many years trying to have the vocation of public relations licensed, elevating it, in his words, "to the level of a profession." The bill he introduced to establish registration and licensing in 1992, when Bernays was 100, did not pass, yet the controversy over licensing continues.

In his letter to colleagues (below), where he urged PR practitioners to review his proposed bill (also below), he asked for the readers' conclusions, be they positive or negative. These suggestions were to help him in drafting another bill he would present in the hope it would pass. Bernays died before he could continue his campaign.

The Museum of Public Relations, while neither carrying the torch of licensing PR practitioners nor attempting to extinguish it, is interested in your point of view. Please answer the questions below and submit before August 31, 1998. Results of this survey will be published on October 31, 1998.

An introduction to Bill #374

By Edward L. Bernays

"The legislative action I urge is in the public interest."

On April 7, 1992, a public hearing before a Massachusetts Joint House and Senate Committee on Government Regulations will address the licensing of public relations practitioners. No legal standard for public relations practitioners currently exists. Anyone can hang up a shingle as a public relations practitioner and often does.

The status quo produces two victims: (1) clients or employers of public relations practitioners who usually have no standard by which to measure qualifications and (2) qualified practitioners whose positions are demeaned by those lacking the experience, education, skills and integrity that true professionals have long labored to attain. Equally important, the public interest is poorly served when those who heavily influence the channels of communication and action in a media-dominated society are inept or worse.

To protect the public and their professions, doctors, lawyers, architects, engineers and other professionals sought licensing and registration from the English Parliament in the early 1880s. Professionalism was adopted soon after within the United States. This action protected both the professionals and the public from the malfeasance of impostors.

Voluntary registration as that proposed by Bill #374 would not infringe on First Amendment rights. Persons passing the licensing exam would be entitled to use a special legalized title that would denote mastery of a body of knowledge and adherence to a recognized code of ethics.

The legislative action I urge is in the public interest. The academic requirements for the new profession of public relations will not affect any presently active practitioner. Public relations curricula in many universities will be modified to meet the criteria of state boards or examiners.

Edward L. Bernays

A call to action from Edward L. Bernays

Dear Colleague:

As you may already be aware, I have spent many years trying to have the vocation of public relations licensed, registered by the state, and ultimately, elevated to the level of a profession. This campaign gained great momentum earlier this year when a bill was introduced to the Massachusetts legislature defining public relations and providing for its license. Bill #374 did not pass. It did, however, give rise to the many voices of support to the issue, as it did many against.

I am presently reviewing the testimonies of support this bill has received. After having also reviewed the objections that many within the public relations vocation have had with this bill, I, and others interested in getting public relations practitioners licensed, will begin to remodel it in hope that a revised bill will pass.

I would greatly appreciate if you could take the time to review Bill #374, and after having reached some conclusions, be they positive or negative, send your comments to me at the above address (see survey below).

Your suggestions will be of great service to me. I have spent much of my life pursuing this goal, and would like to utilize the insights of my colleagues before presenting another bill which I hope will pass.

Sincerely

Edward L. Bernays

The 1992 Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) Convention

The Future of Public Relations

By Edward L. Bernays

"...public relations has suffered from the public's distrust."

I have been requested to speak to you today about the future of public relations and what I see forthcoming in the 21st century.

I am fortunate enough to have followed the field of public relations from its humble beginnings to the vital role it plays in today's society. I am very proud of this vocation and its vital contributions to our democratic society. Public relations embraces the "engineering of consent" based on Jefferson's principle that 'in a truly democratic society, everything depends upon the consent of the public.' This fundamental truth is the basis of my life's work."

I should first state that I feel enormous pride and admiration for the development in public relations in this century, and have great faith in its future into the next. It is a vocation that I hope one day will be elevated to a profession. As of late, however, public relations has suffered from the public's distrust. It is a supreme irony that the vocation that has done so much to foster greater understanding between the private and public interest must now face its own tarnished reputation in the eyes of the public it attempts to serve.

Licensing will benefit Public Relations

Because the words "public relations" are presently in the public domain, anyone, regardless of education, experience, character or conscience can call him or herself a public relations practitioner. This is the primary reason that PR suffers from an unfortunate number of charlatans and incompetents within its ranks. Not only does the status quo leave the public vulnerable to quacks, know-nothings and even anti-social individuals, but it also erodes the legitimacy of qualified practitioners who have long labored to attain the high standards appropriate to this field of practice. "There is a need for public relations practitioners to fulfill certain educational requirements and be held accountable for ethical behavior."

Today, a counsel for public relations does not enjoy the status and responsibility of esteemed professions such as law, medicine, architecture and engineering -- professions which require licensing and registration. Because these are professions, there is an educational requirement beyond the rudimentary body of knowledge. There is a specific regimen of courses required to pass the Bar exam, the Medical boards, and other examinations which define the necessary expertise that uphold the high standards of these professions. Today, no such standards exist for the field of public relations. I believe that there should be. There is a need for public relations practitioners to fulfill certain educational requirements and be held accountable for ethical behavior. This can only be done through licensing.

Licensing will establish the guidelines of the practice and the requirements of a public relations education. That is why I am honored to speak to you, academians and scholars, for it is you who will design the ethical codes and scholastic standards which will define the future of public relations.

Licensing will benefit Society

The needs of a vocation combined with the needs of society dictate the educational requirements of a field of study. But education, in turn, defines the development of a vocation. They go hand in hand. It is hard to imagine, in this day and age, hiring a lawyer who never went to college, or employing an architect who never learned the principles of building design. So, the needs of law and architecture define the educational requirements. Equally so, unlicensed engineers aren't allowed to construct bridges. So, the needs of society dictate the educational requirements.

"Anyone can hang up a shingle and become a legitimate public relations practitioner."

In the early 1800's doctors didn't need to become licensed to practice medicine. Society later recognized the danger of unlicensed, uneducated persons performing surgery on others and introduced licensing. So, in cases where a public could be at risk, or standards had to be maintained, licensing became a common practice.

Though it is unimaginable to allow doctors without licenses to practice, the same does not hold true for public relations counsels. Though the needs of the vocation and the needs of society should dictate the educational requirements of PR, they don't. Anyone can hang up a shingle and become a legitimate public relations practitioner. No standards exist to secure the quality of the practice, nor the safety of the public.

In the case of medicine, the possible danger exposed to one life dictated that doctors had to become licensed. In the case of PR, where millions of lives can be in jeopardy, no such requirement exists. While in the field of medicine, the body is vulnerable — in public relations, it is the mind.

Public Relations must move forward

"[Public Relations] cannot step boldly into the new century without first reevaluating what it is and where it is going to go."

I believe that it is now time for PR to move forward. Public relations has now reached its Rubicon. It has developed into a fully realized interdisciplinary field of study, and is ready to move toward becoming a profession. Progress, however, is being held up by a great deal of dead weight. Because public relations, as a vocation, is saddled with disagreement as to its identity and confusion regarding its direction, it cannot step boldly into the new century without first reevaluating what it is and where it is going to go.

Language is the tool of the public relations counsel, and it is language which must define the path that will carry it forward. It is precise, specific and bold language which must save this honorable profession from floating aimlessly along, slowly stripping itself of legitimacy. The first step in revitalizing the power of language for public relations must be, I believe, in answering precisely these introspective questions.

Public Relations currently lacks identity

"...the term, 'public relations counsel' must be saved from meaninglessness."

Though many have offered definitions for the term "public relations," myself included, few can agree upon one to follow. Because the term has come to mean many things to many people,anything from corporate management consulting to passing around leaflets on the street corner has fallen under the public relations umbrella. Public Relations should not become a catch basin for failed lawyers, unemployed businessmen and inactive stockbrokers hoping for some additional income. The risks to the public and the value of the vocation are too great. I am afraid that without some seriously considered fundamental changes, it will suffer continued erosion of public faith and structural obtuseness.

I believe that the term, "public relations counsel" must be saved from meaninglessness. I believe that one of the primary functions of licensing public relations practitioners will be to define the term and outline the identity. For a public relations counsel to have any validity, he or she must be able to define what they do and how they do it. Though this doesn't benefit the many hostesses, salesmen and managers masquerading as "public relations people," it will benefit the practice, and it will benefit the public.

Defining Public Relations

Since I am held responsible for coining the term, "public relations," I will tackle the opportunity of giving you my definition of it:

A public relations counsel is an applied social scientist who advises a client on the social attitudes and actions he or she must take in order to appeal to the public on which it is dependent. The practitioner ascertains, through research, the adjustment or maladjustment of the client with the public, then advises what changes in attitude and action are demanded to reach the highest point of adjustment to meet social goals.

With this definition in mind, it becomes clear that PR also depends on the formation of a strict ethical code. Ethical behavior needn't be spelled out -- there is no universal definition. Simply put, standard Judeo-Christian ethics, based on integrity and honesty are necessary for a public relations practitioner to properly practice his profession. Doctors must take a Hippocratic oath upon entering their profession, public relations practitioners should do the same.

Returning responsibility to Public Relations

The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court had defined the word profession in a manner illustrating the difference between what public relations is today and what it can be once elevated to a profession.:

"A profession is not a business. It is distinguished by the requirements of formal training and learning, admission to practice by a qualifying licensure, a code of ethics imposing standards qualitatively and extensively beyond those that prevail or are tolerated in the marketplace, a system for discipline of its members for violation of the code of ethics, a duty to subordinate financial reward to social responsibility, and notably, an obligation of its members, even in non-professional matters to conduct themselves of a learned discipline and honorable occupation."

Objections to licensing are based on ignorance

"The opposition to licensing is based primarily on fear."

The issue of licensing for public relations practitioners has brought about much discussion and controversy within the field itself. The candor of the debate, however, has bordered on the hysteric. The opposition to licensing is based primarily on fear. I would like to assuage some of those fears.

Many fear a bureaucratization of what is, in its essence, a social science that is creative in application. This fear is unnecessary. Architects and certified public accountants don't presently wrestle with more bureaucracy than others because of their licensed status.

Others have claimed that licensing is a thinly veiled "witch hunt" to weed out politically undesirable practitioners or to limit the freedom of speech for PR counsels. This is utter rubbish. There are no political overtones to licensing procedures for doctors, lawyers, accountants and other professions. Equally so in this case, there would be none either.

"Those persons who heavily influence the channels of communication and action in a media-dominated society should be held accountable and responsible for their influence."

Also leveled against licensing have been complaints that it would institute unfair competition which would hurt small start-up companies and that it would limit the diversity of experience of public relations practitioners' schooling. First of all, no one is required to license themselves. It is a voluntary act. Secondly, small companies would have no more or less to gain from licensing than anyone else. It is a decision as to what standards a public relations practitioner wants to uphold.

Regardless of education, a defined scholastic requirement would not necessitate undergraduate and graduate work in public relations. PR is a generalist's vocation. An undergraduate degree in English, Advertising, Journalism or other profession would probably suit a career as a public relations counsel perfectly. What is important is that there is some required exposure to Public Relations courses, most likely through pursuing a masters in PR. It is the total lack of experience in public relations education which is the heart of today's problem.

Indeed, licensing does not only protect the public from the misuse of public relations by knowing persons with ill intent. There is an equal danger of the unknowing misuse of public relations, both in name and in practice, by well-meaning, but uneducated ones. This is a field of great social impact. Those persons who heavily influence the channels of communication and action in a media-dominated society should be held accountable and responsible for their influence. Only the licensing and registration of public relations practitioners with the enforcement of a strict ethical code can achieve this aim.

Conflicts of Interest

Unfortunately, public relations organizations have added to the confusion. Those organizations which purport to represent public relations practitioners and their issues are the most wary of defining public relations, lest they lose significant numbers of their membership.

"...there is presently no distinction made between good public relations work and bad public relations work."

In addition, many have their own codes of ethics and behavior, though none are enforceable. To support the licensing of public relations practitioners would undermine their own importance. So, we can expect little support from these groups.

The need for the licensing of public relations professionals also stems from the fact that there is presently no distinction made between good public relations work and bad public relations work. What is considered unethical is not always avoided. What is considered foolhardy is not always dismissed. Clients cannot so easily measure the financial rewards to hiring a public relations practitioner. It is even more difficult to assess whether the work was ethical in execution. If a client cannot differentiate between what is successful and not and what is ethical and not, it is the public relations practitioner's responsibility to. The fact that today these fundamental assessments cannot be made by either party indicates a severe problem.

In this time of increasing complexity and specialization, adopting registration and licensing legislation for public relations practitioners is not just a matter of practical urgency, it is of moral urgency as well.

Public Relations will serve as an example

"...'public relations counsel' will come to represent a beacon of respect and stature in the communications industry."

By licensing public relations practitioners through title registration, there will be no infringement of the First Amendment rights, which no one would want to tamper with, and the title "public relations counsel," will come to represent a beacon of respect and stature in the communications industry. Title registration is voluntary, and will not effect persons in other fields which involve public relations activities. They will, in time, adopt similar practices not because legislation tells them so, but just because it is good business.

I know from a rather long lifetime of experience that good ethics is good business, and that those practitioners who earn their license and uphold the ethical code will be rewarded with very prosperous and constructive careers in public relations.

All that will be secured is a validation of the public relations name, and the establishment of an example of professionalism, ethical business practices and responsible use of the mass communications industry that play such an enormous role in our daily lives.

The future of Public Relations

"...licensing and registration is mandatory if we are to aspire to transform public relations into a respected profession."

In conclusion, I believe that licensing and registration is mandatory if we are to aspire to transform public relations into a respected profession.

I see the purpose of legislation as simply to spark the future development of public relations. The real advances of the field will take place in the school rooms and lecture halls across the country — even the world. The licensed practitioner is not necessarily the competent practitioner. A licensing system is, however, a first step in establishing the direction in which public relations can move forward while held within the framework of its guiding principles. Without these principles and a strict ethical code, PR will be relegated to an increasingly diluted status and waning importance in our society."

"...the 21st Century will reap even greater rewards for public relations and the society it serves."

We have seen what PR can do, and I look forward with great anticipation as to what it will do in the future. I believe that first, we must set the foundation, the springboard if you like, from where the public relations practitioner can move from. With this solid foundation, a new direction can be cleanly forged, and the 21st Century will reap even greater rewards for public relations and the society it serves.

Take the Survey

What are your opinions about PR Licensing?

What follows are several reasons given in support of licensing. For each, indicate whether you strongly disagree, disagree, are neutral, agree or strongly agree.

1994

Edward Bernays at his Cambridge, Massachusetts home, December 1994, age 103.